The Ireland – Leuven Link

The Plantations 15th to 17th Century

The history of early modern Ireland is characterised by political and bitter religious conflict.

For some time the English kings called themselves ‘Lords of Ireland’. Henry VIII (1491-1547) took the title of ‘King of Ireland’ in 1541. Few of the Irish wanted to follow him when he broke with Rome. Resistance to the confiscation of property of the monasteries and other measures strengthened cooperation between the elite classes of the Anglo-Irish and the Gaelic nobility. Under the Tudor monarchs, the English crown contrived several strategies for the pacification of the Island, the best known of which was the Plantations, a policy which involved the settlement of previously occupied lands by English and then Scottish settlers. As the sixteenth century wore on, the religious question grew in intensity and significance.

For some time the English kings called themselves ‘Lords of Ireland’. Henry VIII (1491-1547) took the title of ‘King of Ireland’ in 1541. Few of the Irish wanted to follow him when he broke with Rome. Resistance to the confiscation of property of the monasteries and other measures strengthened cooperation between the elite classes of the Anglo-Irish and the Gaelic nobility. Under the Tudor monarchs, the English crown contrived several strategies for the pacification of the Island, the best known of which was the Plantations, a policy which involved the settlement of previously occupied lands by English and then Scottish settlers. As the sixteenth century wore on, the religious question grew in intensity and significance.

Elizabeth 1(1533-1603) succeeded, albeit with great effort and at great cost, in her goal to establish strong rule and to protestantise the Irish church. The harsh repression and economic measures against the Irish people aroused much displeasure. The Catholic Counter Reformation gained ground. The crisis point of the ‘Elizabethan conquest’ came when the English authorities tried to extend their jurisdiction over the northern territory of Ulster and its Lord, Hugh O’Neill. He enlisted the help of other Irish nobles, and the Spanish monarchy in the person of Philip III who sent an invasion force which subsequently was defeated in 1601. In 1594, the regional rebellion against Elizabeth’s authority gained the support of the King of Spain and the Pope, and more so than had earlier been the case, became infused by religious overtones. In 1603,

Elizabeth 1(1533-1603) succeeded, albeit with great effort and at great cost, in her goal to establish strong rule and to protestantise the Irish church. The harsh repression and economic measures against the Irish people aroused much displeasure. The Catholic Counter Reformation gained ground. The crisis point of the ‘Elizabethan conquest’ came when the English authorities tried to extend their jurisdiction over the northern territory of Ulster and its Lord, Hugh O’Neill. He enlisted the help of other Irish nobles, and the Spanish monarchy in the person of Philip III who sent an invasion force which subsequently was defeated in 1601. In 1594, the regional rebellion against Elizabeth’s authority gained the support of the King of Spain and the Pope, and more so than had earlier been the case, became infused by religious overtones. In 1603,

Elizabeth was succeeded by her nephew, King James VI (1566-1625) of Scotland (James 1 of England). Under James Catholics were barred from all public office, with the consequence that the Irish (both Gaelic and Anglo-Irish) defined themselves as Catholic in opposition to the Protestant colonists and the English authorities. He made peace with Spain following the ending of the Anglo-Spanish war (1585-1604) and also attempted to act as a peacemaker in Ireland, but in this he was obstructed by the Anglican hierarchy, and by special interest groups among the political elite of England. The English blamed the Recusant clergy for the fact that resistance to the state religion still remained. The King permitted the banishment of Jesuits and other groups of Catholic clergy.

Elizabeth was succeeded by her nephew, King James VI (1566-1625) of Scotland (James 1 of England). Under James Catholics were barred from all public office, with the consequence that the Irish (both Gaelic and Anglo-Irish) defined themselves as Catholic in opposition to the Protestant colonists and the English authorities. He made peace with Spain following the ending of the Anglo-Spanish war (1585-1604) and also attempted to act as a peacemaker in Ireland, but in this he was obstructed by the Anglican hierarchy, and by special interest groups among the political elite of England. The English blamed the Recusant clergy for the fact that resistance to the state religion still remained. The King permitted the banishment of Jesuits and other groups of Catholic clergy.

Philip III (1578-1621), the Spanish king supported the Irish rebels in their struggle against English rule and Protestant evangelisation, in 1604 he made peace with James 1. Nevertheless, even after this he still took in Irish refugees. He was the most important benefactor of the Irish Franciscans in Leuven, to whom he promised a continual annual subsidy of one thousand ducats.

Philip III (1578-1621), the Spanish king supported the Irish rebels in their struggle against English rule and Protestant evangelisation, in 1604 he made peace with James 1. Nevertheless, even after this he still took in Irish refugees. He was the most important benefactor of the Irish Franciscans in Leuven, to whom he promised a continual annual subsidy of one thousand ducats.

Continuation of the repression drove large numbers to flee to the continent, among who were some of the most important Irish political leaders, Hugh O’Neill, earl of Tyrone, and his brother-in-law Rory O’Donnell, Earl of Tyrconnel. The nine years war finally concluded with the defeat of the Irish side led by O’Neill with Spanish support in the Battle of Kinsale 1601. Hugh O’Neill finally submitted to the English crown in 1603. However, he and the other earls still harboured the hope that Spain would rally again to the Irish cause. It was not to be. O’Neill and his allies left Ireland in 1607 in the famous ‘Flight of the Earls’, and their lands were confiscated and colonised, becoming the Ulster Plantation.

Continuation of the repression drove large numbers to flee to the continent, among who were some of the most important Irish political leaders, Hugh O’Neill, earl of Tyrone, and his brother-in-law Rory O’Donnell, Earl of Tyrconnel. The nine years war finally concluded with the defeat of the Irish side led by O’Neill with Spanish support in the Battle of Kinsale 1601. Hugh O’Neill finally submitted to the English crown in 1603. However, he and the other earls still harboured the hope that Spain would rally again to the Irish cause. It was not to be. O’Neill and his allies left Ireland in 1607 in the famous ‘Flight of the Earls’, and their lands were confiscated and colonised, becoming the Ulster Plantation.

The College in Leuven

The First Irish student registered in Leuven in 1548. On the 29th of August 1548 Guilelmus Trehesse registered with the rector, in the Liber quartus intitulatorum, as a student in the teaching house and residence of the Castle (Castrum). In the same academic year Richard Creagh (1523-1586?), later the archbishop of Armagh and martyr, matriculated. As political-religious tension in Ireland grew, so the number of Irish students in Leuven increased.

Dermot O’Hurley (ca. 1532-1584) was a typical representative of the first generation of Irish Counter Reformation exiles. Having received his formation in Leuven, where he studied arts and law, and was a professor of pedagogy for fifteen years, he received his doctorate in Reims, went to Rome and was appointed the archbishop of Cashel. He was immediately arrested on his arrival in Ireland. He died a martyr’s death, as a victim of the Elizabethan repression,

Peter Lombard was in Leuven for the first time in 1575, becoming a professor in the Falcon’s (Falco) student residence and after that in the faculty of Theology: In 1600 he went to Rome, a year later becoming the archbishop of Armagh, and was named Primate of Ireland. However, he was never able to return to Ireland.

Thomas Stapleton (1622-1694) was elected seven times as Rector Magnificus by the faculties of law and Medicine

The Earls in Leuven

Because the weather and the condition of the roads prevented them from travelling further to Rome, which was their goal in order to enlist the help of the Pope, O’Neill and O’Donnell passed the winter of 1607-1608 in Leuven. The duke and duchess Albrecht and Isabella in the Netherlands, who expressed great sympathy for the Irish cause, hosted them. At the court, the exiles also met Charles III of Croy, who received them in his castle in Heverlee near Leuven. There they encountered a small Irish colony.

With the growing crisis in their own country, the number of fellow compatriots who followed the example of this first student increased in ever-greater numbers. In a short time, Leuven became the place where the largest number of Irish Catholics was educated. A majority of first generation Irish bishops of the Counter Reformation were alumni of Leuven. Some of them died as martyrs for the Catholic faith, others made careers in Leuven or else in Rome.

Florence Conry

The Franciscan Florence Conry (1560-1629) was one of the confidants of the exiled Irish leaders. Philip III of Spain appointed him advisor for Irish affairs in his Council of the State. Florence Conry came on a mission to Leuven in 1605, and in the following year managed to obtain the support of his order for the idea of building a missionary college in Leuven. He received financial and moral support from the king. Philip III sent warm testimonials for Irish refugees to the archdukes of the Southern Netherlands, and particularly recommended the Franciscan Florence Conry, who wanted to found a college in Leuven.

The Franciscan Florence Conry (1560-1629) was one of the confidants of the exiled Irish leaders. Philip III of Spain appointed him advisor for Irish affairs in his Council of the State. Florence Conry came on a mission to Leuven in 1605, and in the following year managed to obtain the support of his order for the idea of building a missionary college in Leuven. He received financial and moral support from the king. Philip III sent warm testimonials for Irish refugees to the archdukes of the Southern Netherlands, and particularly recommended the Franciscan Florence Conry, who wanted to found a college in Leuven.

At the request of Florence Conry, who had sketched the cliff cult situation of the Irish Catholics, Pope Paul V (1552-1621) on April 3rd’ 1607 approved by Papal Bull the foundation of a College in the University of Leuven with a view to instructing Franciscans who would work in the Irish mission. He refers to the support of King Philip III. In spring 1607, Florence Conry and his colleagues settled in a house, a temporary building, near Saint Anthony’s Church. In the Pig market. The Arts Faculty allowed the Irish Franciscans to use the Chapel of St Anthony and the liturgical vestments that were preserved there; the friars also received a supply of communion wine, and were allowed to build a thoroughfare between the house and the chapel.

The college was opened in 1607. In 1617 the archdukes laid the first stone for the permanent house in Pig Market (‘Varkensmarkt’), which is at present called the Pater Damiaanplein. Saint Anthony of Padua is the college patron.

The college was opened in 1607. In 1617 the archdukes laid the first stone for the permanent house in Pig Market (‘Varkensmarkt’), which is at present called the Pater Damiaanplein. Saint Anthony of Padua is the college patron.

On May 28th, 1616, Philippa de Longin, wife of Filibert van Cranendonck, sells to Jan Baptiste de Spoelberch lands just inside the old city walls, near the beginning of the Broekstraat. Two days later, Spoelberch declared that he had purchased these lands for the Irish Franciscans in order to realise their intention of building a final dwelling place. The Leuven patrician). Spoelberch was a syndicus of the Leuven Franciscans and apparently also of the Irish friars

The archdukes supported this project in various ways, and on May 9th 1617, they laid the foundation stone for the final building of the friars.

Florence Conry had studied in Salamanca and returned in 1601 to Ireland together with the Spanish invasion army. Back in Spain, he was chosen Provincial of Ireland by the general chapter of the Franciscans, In 1606-1608; he came with recommendation letters from Philip III to the Netherlands and founded the Leuven College. Together with the earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnel he travelled to Rome and in 1609, where he was ordained archbishop of Tuam. Via Spain he returned in 1616 to Leuven, where he remained in the college for ten years. On his return to Madrid, he died. A quarter of a century later, his bones were buried in St Anthony’s Chapel, where he also was given a commemorative stone.

The college in Leuven, with Antonius of Padua as a patron saint, became the mother college of six other colleges of the Irish Franciscans on the European mainland, and it was the first institution of its kind founded by the Irish friars. Following this example, a college for the Irish Dominicans, and one for the education of the secular clergy was founded in Leuven. The Carmelites also started a missionary college, which was, however, not only for Irish friars. In addition, other colleges also gave refuge to Irish students. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Irish and the Dutch were the largest group of foreign students at the University. Some of them became professors.

The French Republic closed the college in 1796. However. The Friars managed to remain in residence until 1822. They were able to buy it back and repair the building a century later. Their work has been continued by the new Leuven Institute For Ireland in Europe, which has existed since 1986.

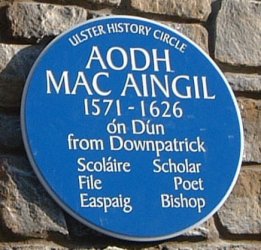

Aodh Mac Aingil 1571-1626

Aodh Mac Aingil was the pen name of the Franciscan scholar, poet and controversialist Aodh Mac Cathmhaoil (his name is usually anglicised as Hugh McCaghwell). He was born in “the City of Downe” in 1571, at a time when the fortified town now known as Downpatrick was a stronghold of the O’Neill’s. We know little of his early life, except that he studied the liberal arts in a school in the Isle of Man, most probably St Mary’s Castletown.

Aodh Mac Aingil was the pen name of the Franciscan scholar, poet and controversialist Aodh Mac Cathmhaoil (his name is usually anglicised as Hugh McCaghwell). He was born in “the City of Downe” in 1571, at a time when the fortified town now known as Downpatrick was a stronghold of the O’Neill’s. We know little of his early life, except that he studied the liberal arts in a school in the Isle of Man, most probably St Mary’s Castletown.

On his return to Ireland Aodh was employed as tutor to the children of Aodh O Neill [Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone] in Dungannon. When O Neill decided to send his eldest son, Ainri, to Spain, perhaps as a covert way of seeking aid from the Spanish king, he sent his tutor with him. The two men lodged in the Convent of the Friars Minor Observantine in Salamanca, while attending the university in the city.

After O Neill’s defeat at Kinsale in 1603, Ainri joined the Spanish Army. Aodh entered the Franciscan Order, and was ordained a priest in 1605. In the sane year he was appointed chaplain to the Spanish Army in Salamanca, a post he combined with lecturing in the University.

At that period the Spanish controlled much of the Netherlands, and in 1607 the Irish College in Louvain, St Anthony’s, was founded for the education of Franciscan priests for the Irish Province. Aodh appears to have been deeply involved in this project, and was transferred to Louvain as its first lecturer in philosophy and theology.

It seems that the nick-name Mac Aingil, ‘son of Angel’ invented by his students Aodh used this as his pen-name to the most famous of his Irish-language writings, his Scathan Shacramuinte na hAidhridhe [A reflection on the Sacrament of Penance] published in Louvain in 1618. This work reflects the dialect of Irish spoken in east Down at the time, but is chiefly admired for its limpid, elegant and accessible style, a striking marriage of classical and colloquial registers.

Aodh was apolitical moderate, supporting King James 1, the son of Mary Queen of Scots, as the lawful king of Ireland as well as England, Wales and Scotland. He emphasised the king’s Christian theology and pointed out how minimal were the errors of his faith, hoping time would remedy them.

He and his fellow Franciscans were nevertheless extremely active in the Counter-Reformation, setting up a printing press for religious books in Irish and smuggling them into Ireland. The Franciscans of St. Anthony’s College played a unique role in the preservation and study of the Irish language and culture. They installed their own printing press and had a specific Irish printing font made. Hugh Ward, John Colgan and mainly the lay brother Micheal O’Clerigh collected and copied the old Irish texts, which, among other things, led to the editorship of the Annals of the Four Masters, a compilation which preserved an important part of the medieval Irish heritage.

His contemporaries held Aodh in high esteem as a philosopher and theologian; he published thirteen books in Latin, including an edition of the works of John Duns Scoots. By 1623 his reputation had grown to such an extent that he was appointed professor of divinity at the Convent of Ara Coeli in Rome. He travelled on foot-from Louvain to Paris and from there to Rome to take up his new post.

On the death of Peter Lombard, Archbishop of Armagh, Aodh Mac Aingil was nominated as Archbishop of Armagh in April 1626 and was consecrated by Cardinal Gabriel Trejo on 7 June. The new archbishop began a pilgrimage of the seven chief churches of Rome but became ill. Returning to Ara Coeli he lay under a fever from which he died on 22 September 1626. Ireland never enjoyed the privilege of having this brilliant and holy man as primate.

Acknowledgement: This account was collated with the kind assistance of Professor Rogiers and Colleagues at KU Leuven